Where do things stand with the Trump Administration and U.S.-Cuba relations?

Recall that President Donald Trump and Vice President Mike Pence made clear, as candidates, that without concessions from Cuba’s government, they would reverse President Obama’s major changes in U.S.-Cuba relations on Day One. This threat continues to rattle Cubans.

President Raúl Castro, speaking in January, made clear that no one should expect Cuba to “renounce its ideals of independence and social justice or abandon any of our principles, or give in an inch in the defense of our national sovereignty.”

Even though the battle has yet to be joined, we’ve seen this array of forces before: the immutable force of Washington’s demands for existential changes in Cuba’s system poised to collide with the immovable object of Cuban sovereignty.

To be clear, we are 43 days in and the administration has made no changes to the policy. We’re not trying to jinx that. We’re trying to understand it. The administration is going out of its way to honor campaign promises. It is stocked with embargo defenders. Key leaders in Congress support rolling back travel and trade reforms and beefing up programs to take down Cuba’s system of government. We expected to be disappointed and playing defense much sooner.

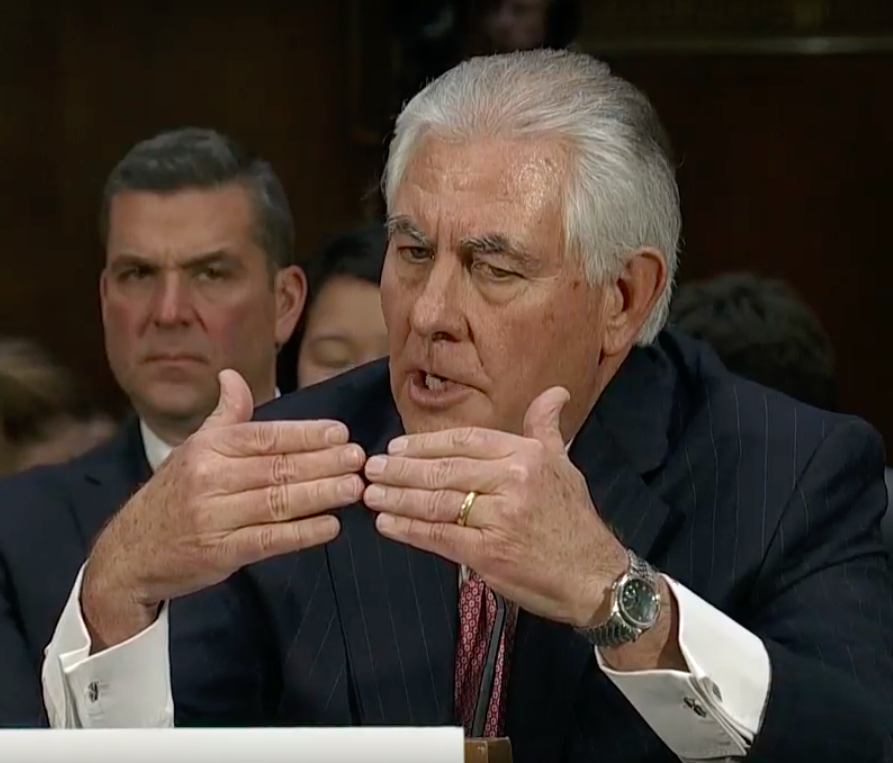

One explanation could be disarray in the foreign policy machinery. As we discussed last week, the President has his second National Security Advisor in his young administration. The White House fired Craig Deare, its senior national security advisor on the Western Hemisphere, just two weeks ago. The Washington Post is asking, “Where in the world is Secretary of State Rex Tillerson?” and gamely reporting that “Tillerson’s diplomacy has been conducted out of sight.” This is the man in charge of the Trump administration review of Cuba policy.

The State Department, according to The Atlantic‘s Julia Ioffe, has the comparative feel of a ghost town. She writes, “There hasn’t been a State Department press briefing, once a daily ritual, since the new administration took over five weeks ago.” Observing that the briefings are not just for journalists, Ioffe says the silence from the State Department podium deprives U.S. diplomats all over the world of a “crucial set of cues…With no daily messaging, and almost no guidance from Washington, people in far-flung posts are flying blind even as the pace of their diplomacy hasn’t abated.”

For a host of reasons that go beyond our interest in Cuba, it is unfortunate that we don’t have in place the traditional structures to mediate or understand what is happening with U.S. foreign policy.

The President, in his inaugutal address, kicked the concept of sovereignty into play when he said, “We will seek friendship and goodwill with the nations of the world — but we do so with the understanding that it is the right of all nations to put their own interests first.”

This week, in his first Joint Session of Congress address, he revisited this subject in much the same way. “We will respect historic institutions, but we will also respect the sovereign rights of nations. Free nations are the best vehicle for expressing the will of the people — and America respects the right of all nations to chart their own path.”

At the same time, in the Trump administration’s forthcoming FY2018 budget request, the White House is proposing a 30% cut in State Department funding and a 40% cut in USAID funding to help prioritize a sharp increase in defense spending. Priorities which have prompted some critics to call the President an “isolationist” or a “militarist”.

Again this week, in what the Washington Post described as a “sharp break from U.S. trade policy,” the Trump administration said it may ignore “certain rulings by the World Trade Organization if those decisions infringe on U.S. sovereignty.”

If sovereignty is the defining principle of Trump administration foreign policy, that is resonant with implications for the Page One issue of Russia and for our principle concern, Cuba.

In an article published last year by Vox, Fiona Hill, a former U.S. national intelligence officer for Russia, examined the motivation behind President Putin’s campaign to hack the U.S. elections. Ms. Hill wrote, “Putin wants the United States and other Western governments to stop funding, as part of their foreign policies, organizations that promote political and economic transformations in Russia. He also wants to block U.S. officials from meeting with opposition figures and parties. From Putin’s perspective, democracy promotion is just a cover for regime change.”

Most Americans don’t like Russia’s interference in our democratic process. This isn’t about moral equivalence: it’s natural for people to want to protect their nation’s governance from outside interference. While it may be a permanent part of our national character to preach to others about the value of our system – and it has value — it is something entirely different to try and impose it on others. This is where we hope the Trump doctrine’s devotion to sovereignty extends.

The U.S. has a long history of trying to overthrow the Cuban system through measures that included the Bay of Pigs invasion, covert operations, efforts of the kind that landed Alan Gross, the former USAID subcontractor, in a Cuban prison for five years, and more. President Obama’s Cuba policy put an end to most of that. Now, advisors to the new administration, such as José Cárdenas, who testified before Congress this week, want President Trump to exert economic pressure on the Cubans and bring the old policies back. The administration will probably do so.

Yet there is another, more hopeful course, and both presidents have spoken to it. In the remarks we quoted above, President Raúl Castro also said, “As I have repeatedly affirmed, both Cuba and the United States should learn the art of civilized coexistence based on respect for differences between our governments, and on cooperation in areas of common interest that may contribute to tackling the challenges facing the hemisphere and the world.”

For his part, President Trump told the U.S. Congress, “America is willing to find new friends, and to forge new partnerships, where shared interests align. We want harmony and stability, not war and conflict. We want peace, wherever peace can be found.”

If Rex Tillerson can be found, he might suggest to Bruno Rodríguez, his Cuban counterpart, that sovereignty could be just the thing to bring the two leaders together.

This column was first published in the Cuba Central blog of the Center for Democracy in the Americas