CUBA STANDARD — European countermeasures designed to blunt expanded extraterritorial sanctions by the Trump administration against Iran and Cuba have failed, says an analysis published by a think tank close to the German government.

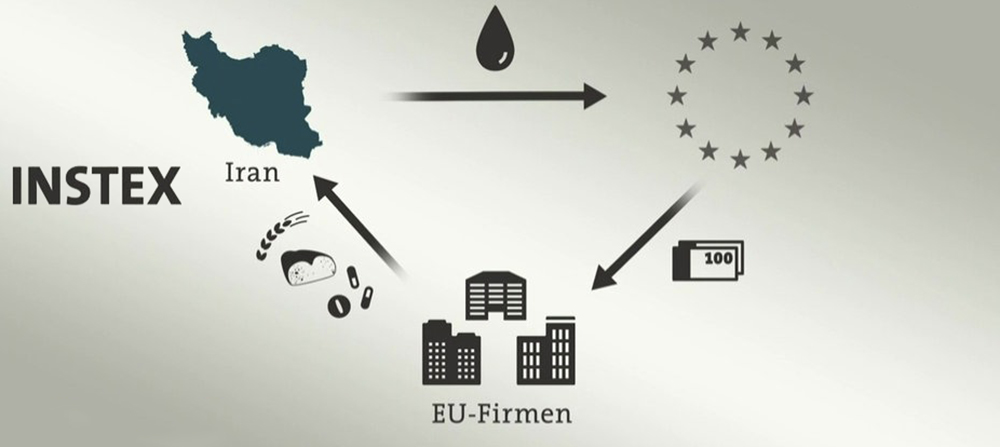

The INSTEX barter mechanism that was supposed to facilitate trade with Iran by circumventing U.S. financial sanctions is not finding major takers, and a reactivated 1996 Blocking Statute has been unable to protect — unwilling — European companies from Helms-Burton Title III lawsuits in U.S. courts, says Sascha Lohmann, a U.S. expert with the Berlin-based Stiftung für Wissenschaft und Politik.

Reeling from billion-dollar U.S. penalties and threats of being cut off from the U.S. market, European banks overeagerly avoid any possible clashes with U.S. sanctions. Even the European Investment Bank (EIB), the bloc’s main development finance vehicle, has outrightly refused to extend loans to Iran projects, and has yet to activate funding for projects in Cuba, nearly two years after it was directed to do so.

In addition to setting up mechanisms that allow strategic autonomy, EU leaders should therefore consider using existing venues such as U.S. courts, Lohmann recommends.

“One possibility would be to support European companies diplomatically and financially in seeking U.S. courts to restrict the enforcement of national laws beyond U.S. borders,” he says in his analysis. “Only U.S. courts are able to effectively limit the worldwide enforcement of national law.”

Instead of settling, European companies accused of violating sanctions abroad should let their cases play out in court, he suggests, as the United States, using several legal concepts rooted in national law, acts in a gray zone.

To be sure, no such challenge has been brought to U.S. federal courts yet, let alone the supreme court. Also, this would clash with a long-standing practice of expanding the reach of U.S. laws, which ultimately led to the severe U.S.-EU crisis over Iran. Finally, European corporations are unlikely to risk taking their case to court.

“In fact, many U.S. federal courts support the administration’s global take on enforcement,” Lohmann admits. “Usually, they do not weigh the interests of the United States and those of other nations. Most foreign defendants accused of violating U.S. law abroad prefer to avoid a criminal case and sign a deferred prosecution agreement, under which they submit to civil measures by the U.S. administration.”

This is why Lohmann suggests public corporations such as the EIB could take a lead. The reason making it worthwhile taking the legal gamble is the supreme court’s recent use of the concept of “Presumption Against Extraterritoriality” in determining the extraterritorial reach of U.S. law, he says.

The principle “would give defendants accused of violating U.S. laws abroad a powerful lever: They could argue that U.S. laws do not apply to them or their actions. Conservative Supreme Court and lower-instance judges would probably be receptive to such an argument because they favor a literal interpretation of the U.S. constitution and are deeply skeptical of the expansion of administrative state functions over the past 60 years.”

“In practical terms, this means to systematically encourage EU companies and then support them to challenge” the reach of U.S. laws in U.S. courts, Lohmann writes. “This approach would first be an option for government-related enterprises such as EIB or INSTEX, and would have to be coordinated closely between the European Commission, member states and the private sector on both sides of the Atlantic.”

Finding ways to protect European companies against U.S. sanctions and incentivizing them to do business in sanctioned countries has gained additional urgency in Brussels as the U.S.Congress is working on a comprehensive package of sanctions against Russia, a major trade partner of EU member nations and particularly Germany.