Amid the isolation caused by U.S. sanctions, Cuba has built a pharmaceutical industry that not only supplies Cuban patients with medicine, but also generates the country’s No. 2 goods export after nickel. Most of the international attention has focused on Cuba’s cutting-edge biotechnology such as cancer vaccines. However, 30-some years into the initiative, observers question whether this biotech industry is sustainable. Despite decades of massive investment, annual exports of all pharmaceuticals probably don’t even cover the cost of maintaining research, development and production in Cuba. Not a single Cuban pharmaceutical product has yet achieved approval in North America, Europe or Japan, which make up some 80% of the world’s pharmaceutical sales.

Amid the isolation caused by U.S. sanctions, Cuba has built a pharmaceutical industry that not only supplies Cuban patients with medicine, but also generates the country’s No. 2 goods export after nickel. Most of the international attention has focused on Cuba’s cutting-edge biotechnology such as cancer vaccines. However, 30-some years into the initiative, observers question whether this biotech industry is sustainable. Despite decades of massive investment, annual exports of all pharmaceuticals probably don’t even cover the cost of maintaining research, development and production in Cuba. Not a single Cuban pharmaceutical product has yet achieved approval in North America, Europe or Japan, which make up some 80% of the world’s pharmaceutical sales.

Possibly the foreigner with most first-hand experience in Cuban biotech is David Allan, a Canadian and former investment banker specializing in biotech, whose relationship with Cuba goes back nearly 25 years. In 1994, impressed by Cuba’s potential, Allan created YM BioSciences, and raised some $300 million in the course of 15 years for the development of two Cuban cancer vaccines. Even though YM pulled back from Cuban products in 2011, no other foreign partner has been able so far to replicate its achievements.

That does not mean Cuban biotech has come to a standstill. Malaysia’s Bioven continues with Phase-3 trials of CIMAVax in Europe, and more recently Buffalo-based Roswell Park picked up development of the cancer drug for the North American market. Meanwhile, Cuba has continued to diversify its partnerships, most importantly through biotech agreements with China such as a $307 million fund for joint drug development.

Cuba Standard Editor Johannes Werner recently asked David Allan — who now is a principal of Toronto-based Creswell Advisors — about Cuba’s biotech challenges and prospects.

How did you get into the Cuba business?

In late 1993, we were invited by the Consejo de Ministros to review the “bio-establishment” in Cuba and propose an arrangement to assist with the commercialization of its output. The Russians had withdrawn approximately two years prior, and there were few or no relationships within the pharmaceutical industry in the major-market countries. However, our review of the deep science, the facilities and the uniquely collegial organization of the Polo Científico astonished us.

No other country in Latin America had the disciplines and structures that the Cubans had established, largely as a result of Fidel’s focus on the area. One of the unique elements was that in the rest of the world, including the United States, Canada and Europe, basic research principally resulted from an academic environment, unlinked from considerations about ultimate commercialization and manufacturing. At the Polo Científico, manufacturing and marketing was built on top of the research functions, physically in the same building. That was an absolutely brilliant step — something the rest of the world could very much benefit from. They would only concentrate on the research concepts that they believed had commercialization potential. And cooperation between the scientific centers was equally unique. As a result of our extensive review, we recognized that the impediment to commercialization would be the absence of data on Cuban products generated in the target-market countries — Europe, North America, Japan — and we proposed a joint venture precisely to perform that function and, particularly, to provide access to capital for its execution.

How did you structure the joint ventures with Cuba?

In late 1994, after a number of team visits, we proposed a JV structure in which the government would contribute commercialization rights to five products we selected into five separate Canada-based joint venture subsidiaries of YM BioSciences. Together with its Cuban counterparts, YM would design and conduct clinical trials in its territories for which it would be responsible for raising all the money. Manufacturing would remain solely in Cuban hands. Upon commercialization YM would receive 80% of the benefit and the Cuban partners 20%. But, since the partners retained manufacturing, the economics likely approached 50-50 — which supported the willingness for Cuba to adopt the formula. The JV proposals were approved by the Consejo de Estado in May 1995 on the basis that YM would raise the agreed initial financing within a short period. However, it was extremely difficult to convince investors of a novel arrangement in a jurisdiction that was unfamiliar and with a political landscape foreign to them.

Until you got help from a popular former Prime Minister…

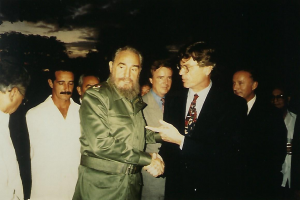

We faced the possibility of having to negotiate extensions to the JV agreement and we particularly needed a mantle of respectability. We were very fortunate that Canada’s former Prime Minister, Pierre Trudeau, agreed to support us. So, in September 1995, I organized two chartered planes to fly us to Havana with him, members of the government of Saskatchewan, and members of the law firm where Mr. Trudeau was resident, to meet with Fidel at a dinner organized by our ambassador at the official residence. Five days later, on the plane on the way back to Toronto, I got commitments for the first $2.5 million, led by the government of Saskatchewan’s Opportunities Fund. That was just the beginning of the $300 million we raised eventually.

Although YM was about Cuban-origin products, you were able to raise that kind of money mainly in the U.S. market. How did you achieve that?

Raising money for Cuban-origin pharmaceuticals unknown in the “Western” pharmaceutical world was extremely challenging. We had to persuade investors that, risk-adjusted, the financial returns were equal or superior to biotechnology in North America, in which there was plenty of opportunity. There are hundreds and hundreds of innovative companies in North America for investors to choose. It was a hell of a struggle. The investment bank in which I was a senior partner was a leader in mining finance. Consequently, we were both familiar with Cuba and known by the Consejo de Ministros. Additionally, Sherritt had already established a very high profile in nickel so that the geography was not unfamiliar to Canadian investors. Three recognized Canadian funds put up the transformational capital of about $15 million in 1997 after our seed round of late 1995, and a biotech-specific intermediary, Clubb Capital in the UK, arranged for $17.5 million from a Swiss investment group in 1999. Because Europe is known to be more international in its investment appetite than Canada, our subsequent $15 million IPO actually took place on the London Stock Exchange in 2002. Because we had diversified our portfolio to include in some hugely attractive non-Cuban cancer therapeutics, appetite for our shares was sufficient for us to place two U.S. financings in 2003 and 2004, each some $20 million and almost entirely in New York. These were, to our knowledge, the first two financings for any Cuba-related organization in the U.S. capital markets, and the 2004 financing was accompanied by our listing on what was then the American Stock Exchange.

Raising money for Cuban-origin pharmaceuticals unknown in the “Western” pharmaceutical world was extremely challenging. We had to persuade investors that, risk-adjusted, the financial returns were equal or superior to biotechnology in North America, in which there was plenty of opportunity. There are hundreds and hundreds of innovative companies in North America for investors to choose. It was a hell of a struggle. The investment bank in which I was a senior partner was a leader in mining finance. Consequently, we were both familiar with Cuba and known by the Consejo de Ministros. Additionally, Sherritt had already established a very high profile in nickel so that the geography was not unfamiliar to Canadian investors. Three recognized Canadian funds put up the transformational capital of about $15 million in 1997 after our seed round of late 1995, and a biotech-specific intermediary, Clubb Capital in the UK, arranged for $17.5 million from a Swiss investment group in 1999. Because Europe is known to be more international in its investment appetite than Canada, our subsequent $15 million IPO actually took place on the London Stock Exchange in 2002. Because we had diversified our portfolio to include in some hugely attractive non-Cuban cancer therapeutics, appetite for our shares was sufficient for us to place two U.S. financings in 2003 and 2004, each some $20 million and almost entirely in New York. These were, to our knowledge, the first two financings for any Cuba-related organization in the U.S. capital markets, and the 2004 financing was accompanied by our listing on what was then the American Stock Exchange.

What about U.S. sanctions against Cuba?

As you can imagine the legal bills to establish the ability of U.S. investors to buy our shares were monumental, but we succeeded. The FDA clearance of our clinical trial application in 2004 — the first in history to our knowledge — was pivotal for the recognition by the market that our Cuban relationships had achieved a breakthrough moment. From a capital markets incentive perspective, the FDA’s Orphan Drug Designation for Nimotuzumab two weeks later was astonishing and validation of YM’s prospects. A 2006 financing of $40 million led by Cowen & Co in New York was helped considerably by a brief article in Forbes. But much of the attraction for U.S. investors was a novel Canadian therapeutic for metastatic breast cancer. So its tragic failure in the pivotal Phase-3 trial predictably resulted in a share price collapse. What is fascinating is that the rebirth of the company was made possible by $15 million financing in 2010 in the United States based on Nimotuzumab. We had previously launched U.S. trials in children with inoperable brain cancer in 2009, but what provided the appetite for the 2010 financing was another breakthrough when the U.S. Treasury Department lifted limits on the trials we could conduct in the United States with the drug. Additionally, at that time, 32 Nimotuzumab clinical trials were ongoing worldwide, one-third of which were being conducted by YM and its licensees. Between 2010 and 2011, we raised an additional $130 million, stimulated in part by our acquisition of an Australian oncology company. But our history and our commitment to providing a bridge to the world’s capital markets for the development of Cuban therapeutics remains unmatched by any other company to this day.

Why did YM Biosciences expand beyond Cuba?

It became obvious at the time that solely concentrating on the Cuba story was very difficult. Also, the YM model, which was taking other people’s research and committing to its development, was a model that was not widely practiced at the time. It was important for the continuum, both for the Cuban products and the company, that we expand the portfolio beyond Nimotuzumab and CIMAVax. But we did all of this while working with our Cuban allies. Don’t forget that YM had five international sub-license holders conducting, together with us, 11 trials worldwide. Three of those were at the final stages – Phase 3. Funding all this would not have been possible without our having positioned YM as an attractive investment vehicle.

Even so, you and your successors failed to achieve the ultimate goal …

Yes. Nimotuzumab has been well tested and although it is available in, I believe, 28 countries, it’s not available in a single highly-regulated market. It’s hard to say why our substantial investment did not persuade regulators. That is nothing specific to Cuba or the drug. It happens all the time to multinationals — Astra Zeneca, Bristol Myers, Roche — the list is long.

Describe the clinical testing process.

When you put a product into the regulatory process aiming to market a drug, you go through three phases. Phase 1 has to prove it’s safe, something that could take one to two years. Phase 2 has to prove it’s safe and actually provides a benefit for the patient – perhaps 200 patients and two to three years. And Phase 3 has to confirm what it did in Phase 2 but this time through blind testing where even the doctors don’t know who is getting the drug and who is getting placebo. This stage of trials could involve anywhere from 500 to thousands of patients in multiple hospitals around the world. In cancer you can spend 10 to 15 years sticking drugs into people; the pharma industry milestone cost is in the region of $1.5 billion. That’s what the process takes. And once the regulators have looked at your data, and decided whether they think it’s good enough to be approved for marketing, less than 10% of what starts makes it out at the other end. One in 10-15,000 discoveries of new molecules or processes makes it to the clinic, and then less than 10 of each 100 in the clinic makes it to market. So it’s not just costly but a very risky business.

Why is clinical testing and approval in major markets so important?

The only test of the value of a medicine is data from clinical trials — what happens when you treat patients with a research drug, and is it safe? You hear innumerable stories about this breakthrough or that, but it is mostly just not so. Sadly, much of this nonsense has been written by foreign observers about Cuban breakthroughs. Ultimately, unless you generate confirmatory data from trials in humans in what used to be called First-World countries, the product is condemned to the 15% of the world that has less rigorous standards and where the price for the product is lowest.

So, if a product has been approved for the Cuban, Colombian or Malaysian market, that doesn’t mean anything in regards to its efficacy and acceptance?

One hundred percent. The fact that a product is acceptable for Argentina or the United Arab Emirates has no bearing whatsoever in the highly regulated markets. And a number of markets, such as South Korea, require previous U.S. approval before they clear a product for marketing in their jurisdiction.

What about other development companies, such as Malaysia’s Bioven, that have picked up Cuban drugs for clinical trials? Have they maybe raised interest by some big pharma company?

I’ve never been able to find any reports on Bioven’s data since both the Aberdeen and Malaysian trials were terminated, nor have they reported any transaction with a major pharmaceutical company. They announced that they received clearance from the FDA for an arm of their Phase-3 trial in the United States, although there is no listing for this trial on the U.S. government website. Abivax of France terminated the trial on CIGB’s hepatitis vaccine in 2016 for futility. Heberprot-P, announced as a breakthrough in a most severe condition was reported licensed to Mercurio Biotec in Ohio who have made no announcements on progress in 18 months. All of these are tiny companies — not a line-up of the kind that one would say reflects the importance of Cuban breakthroughs. The fact is that there has not been a single pharmaceutical company that has developed or received clearance for marketing Cuban drugs in any major-market country.

You still describe Nimotuzumab, which is now in the hands of Innokeys, as a promising drug. But it’s been tested for more than two decades; does it mean it’s reaching the end of its run for highly regulated markets?

The answer would be yes. Erbitux, the first drug of its class, was launched in the United States in 2004, with peak sales close to $2 billion a year. The reason we were so enthusiastic about Nimotuzumab is because it did not have any of the severe, debilitating side effects that Erbitux had. If it were demonstrated to be as effective as Erbitux, it should presumably have been able to be registered. Even though Daiichi Sankyo and Oncoscience, a European sub-licensee of YM, took the drug into Phase 3, the data, in the case of pediatric brain cancer, did not persuade the regulators sufficiently to approve commercialization. Daiichi Sankyo actually terminated Phase 3 in 2014, because of severe adverse events. Although the drug is reportedly marketed in numerous countries it has not been registrable in any highly-regulated market. That means it’s probably at the end of its interesting lifetime, bypassed by the numerous advances in the field.

How do you see the prospects for CimaVax under Roswell Park and Bioven?

Bioven announced a year ago that they had received clearance from the FDA to conduct a Phase-3 trial — at about the same time Roswell Park announced they had an agreement with CIM. It became very confusing as to who actually will own the US commercialization rights. Since that announcement by Bioven, there has been no evidence of them having raised any additional capital. That would make it seem very unlikely they would be able to run a Phase-3 trial, because, as we said earlier in discussing trials, that would be large and very expensive. All the information that is available seems to suggest they have not been able to raise any capital since the last round with the Malaysian government. The testing in Britain of CIMAVax as a single agent was terminated. Additionally, single-agent prospects seem to be very doubtful in major-market countries. What Roswell has done is much more constructive. They’re combining CIMAVax with a powerful immuno-oncology agent called PD-1. BristolMyers markets the drug and it’s right at the cutting edge. The combination of CIMAVax and PD-1 is very likely to be effective — to what degree, nobody has any idea. The real issue is whether the addition of CIMAVax to PD-1 is going to increase the efficacy of PD-1 and to what degree? The trial is small and not finished until 2021.

Beyond brand-name drugs and partnering with pharma multinationals, what other options do you think Cuba has to develop its biotech industry?

The thousands of companies in the North American biotech industry raise billions of dollars every year — probably around $20 billion this year alone — for their development programs. YM was acquired for $510 million, and we were just a small company. Cuba doesn’t have access to any money outside its government funding. Everything Cuba has achieved is through skill, talent, dedication and devotion. But ultimately, everything in medical development is about money. Cuba’s pharmaceutical exports generate maybe $100 million-$200 million a year in revenues. This would be sales of multiple products by multiple scientific centers that in turn have a cost of goods. They have to make the stuff, they have to pay their staff, reported as around 22,000, they have to pay electricity. Probably 75% of the biotech companies in North America would raise, just for their own use, more than $100 million. Each year, each one. In the absence of a dramatic change in the approach to accessing capital — the Chinese figured that out long ago — the impediments to success will remain daunting. You do not raise a child by starving it, and Cuba’s scientific skill, talent, passion and vigor cannot be sustained without the constant nutrient of capital.

Is there anything else in the Cuban research pipeline?

I am not aware of a product of a breakthrough nature in recent times. We spoke earlier about Heberprot, the diabetic-foot cure. It doesn’t appear to be going anywhere. We mentioned Abivax and its deal with CIGB for a hepatitis-B vaccine, but that failed in its clinical trial. There is no reference on the Abivax website to anything in relation to Cuba; so the Abivax connection seems to have terminated. I don’t see it. Cuba is a love affair, because of its exotic nature, because of its history, because of its extraordinary people. But the hyperbole that has attended the prospect of Cuban science has been excessive. It doesn’t have the foundations to support a world-competing industry, and the pharmaceutical industry, constantly on the hunt for new products, has yet to announce an agreement with any one of Cuba’s research centers.

You’re doubting the usefulness of Cuba trying to come up with new biotech products?

In an objective economic analysis, it doesn’t make any sense. What they achieved from 1980 onwards was necessary and important — it was exceptional and a breakthrough at the time. Fidel understood that, if the Russians were to disappear, this island would have to become self-sufficient. But the purpose for which this all got going has disappeared. Now Cuba is no longer isolated as it was, I don’t see a prospect of anything exceptional coming out of their work. In cancer, if they’re not at the cutting edge of immuno-oncology, for example, they’re not going to produce anything that’s not available from the U.S., Europe or Japan. There’s no access to capital for anyone in Cuba. Since YM, there’s nobody that has joint ventured with the Cubans in a manner that would have permitted them to retain their political structure and also access capital markets.

Even so, Cuba has, after all, built a biotech industry. What do you think these institutions ought to be doing, short of shutting down?

It’s hugely difficult. The purpose now for these organizations is to generate revenues for the country, by coming up with novel products and manufacturing them for domestic consumption or exporting them, or by manufacturing existing products, generic biopharmaceuticals, that everybody else could make. Cuba says its biotech industry replaces billions of dollars a year of what it would otherwise have to import. But at what cost? One must be skeptical of the economics with the claimed 22,000 employees. And what would set Cuba apart to be competitive for generics? Labor cost would be one, regrettably. But biopharmaceuticals are expensive to manufacture because of the inputs. And the costs of inputs in Cuba are high. I don’t see how they could compete profitably when there are companies around the world that are magnificent at the generics business. I don’t see it. The foundations for this initiative were brilliant. There was a good reason for it, it was exciting, and the scientists and technologists were highly educated and capable. But high science does not make an industry.

And the 15% of the world pharmaceutical sales that aren’t in major markets? There are arrangements with Russia, Brazil, Malaysia, Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates; China and Cuba are partnering now in several biotech ventures — not an option for Cuba?

The major-market countries are, typically, the wealthiest where drug prices, and consequently profit margins, are high. In secondary markets that represent some 15% of the rest of the globe prices are low so I do not see how Cuba can produce an economic return in biologics. Conventional medicines perhaps, but that wouldn’t make much of a story, would it?